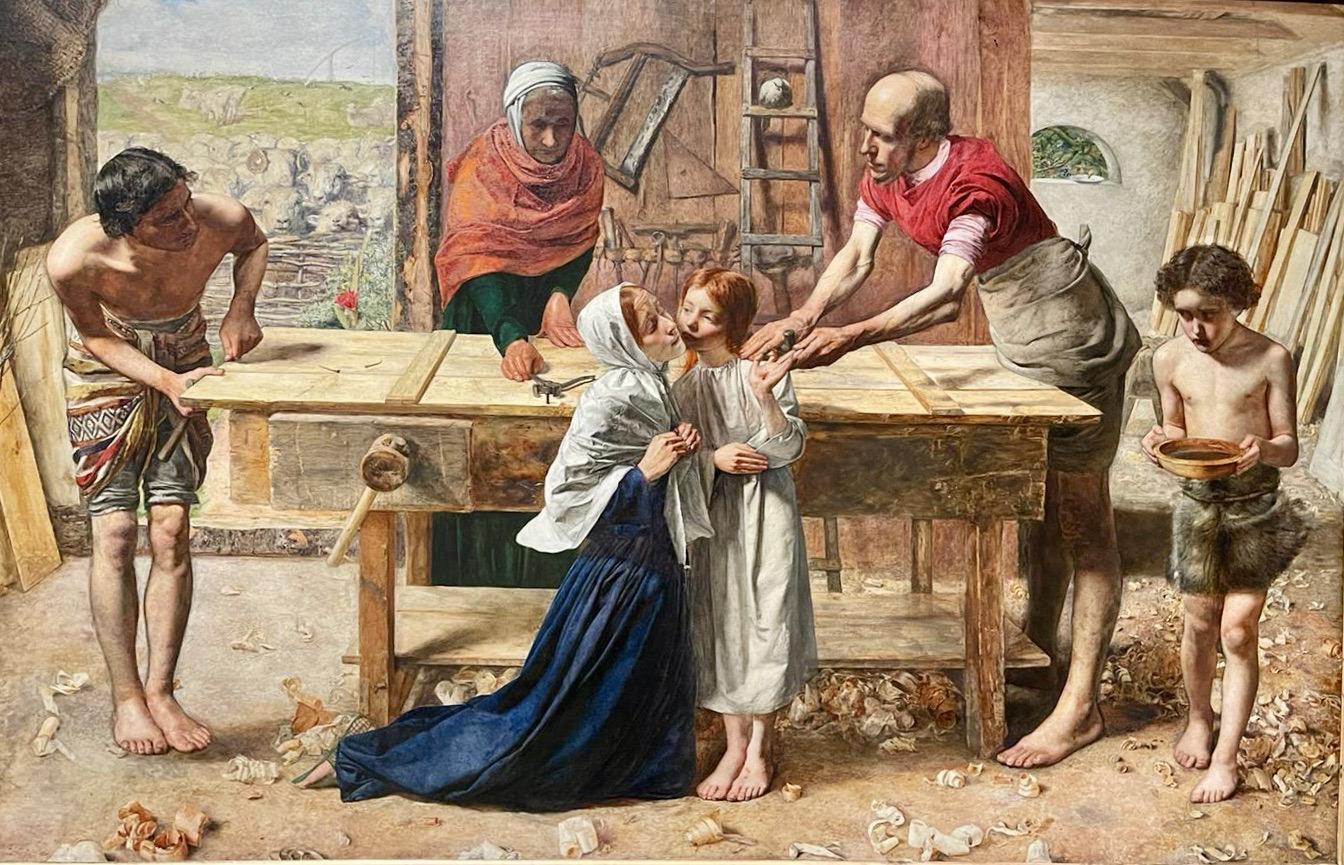

Christ in the Carpenters Shop

This painting by Millais caused an uproar. Charles Dickens led the assault: “Here is a kneeling woman so horrible in her ugliness … she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or the lowest gin shop in England.” Victorians were horrified to see the icons of their faith treated with such realism.

The painting expressed the heart of the revolutionary ideals of the new Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Their aim was to return art to the simple honesty of painting before the High Renaissance: before the dramatic lighting effects of Caravaggio, the dramatic compositional devices of Titian and the idealised perfection of Raphael, which gave rise to so much of the dark, brooding art that decorates Catholic Churches across the continent.

Here the light is plain and simple, with no dynamic shadows; the composition is made of unsophisticated horizontals and verticals, and perspective is captured by the cross braces of the door on the bench, their strong angles pointing to their allotted vanishing point on the centre line of the canvas like the broken spears and bodies in an Early Renaissance battle scene by Uccello.

Mary is no longer the innocent virgin, but an ageing mother deeply, in fact disproportionately, distressed by the cut on her son’s hand, which she recognises as foretelling of his crucifixion. Joseph is not strong, thickly haired and bearded, but a wiry, barefooted carpenter, in vain denial of his age with a few strands of hair combed over his glossy bald head. Even the depiction of the young Christ as a red-head shocked enraged Dickens who described him as, “a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed gown.”

It is painted with the attention to minute detail which is an integral part of the style we associate with the Pre-Raphaelites: every wood shaving on the floor is painstakingly rendered.

But there is fun to be had in deciphering all the details and symbols which prefigure the story to come. Jesus has cut his hand on the head of a nail (one of three) and a drop of blood has fallen onto his foot exactly where the stigmata will eventually be. The young John the Baptist, clothed in traditional goat-skin, is nervously bringing water to bathe the wound rather than to baptise.

And there is more: the set-square handing on the wall symbolises the Trinity; the ladder is presumably Jacob’s with a dove resting peacefully on it prefiguring the dove that appeared at Christ’s baptism. The sheep outside foretell of the flock of which we are to become a part. In the centre of the flock is a ram: perhaps the ram caught in the thicket when Abraham was about to sacrifice Isaac, or the ram in Leviticus which serves as a guilt offering? Maybe even the door they are making prefigures the door to eternal life…

One additional detail intrigues me: there is another splash of thematic red just outside the door in front of the penned sheep. It is the exotic flower on a cactus. The cactus symbolising Jesus’ time in the desert, I presume and the flower – the beauty that was born of that suffering?

You can find this masterpiece in Tate Britain and make up your own interpretations as you enjoy it!