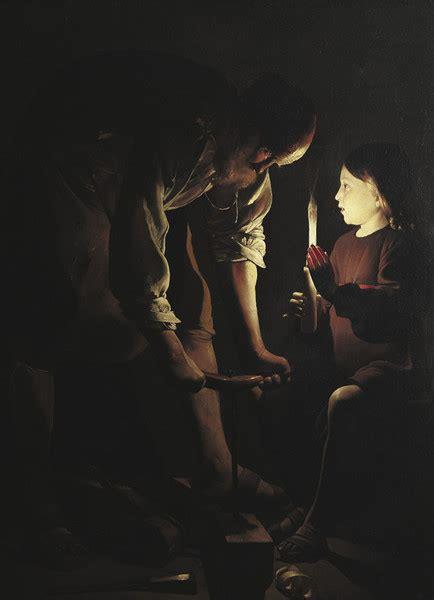

The Carpenter Georges de La Tour

June 2023

One of my favourite paintings in The Louvre is this masterpiece by Georges de La Tour of Joseph the carpenter with his son, Jesus. The dramatic use of light is immediately striking. This form of chiaroscuro, called Tenebrism, is often the hallmark of a Latour painting: a strong light, shaded by Jesus’ hand, throwing the composition into sharp contrasts of light and shade.

Stronger than any normal candlelight, it is a spiritual light rather than a terrestrial one. It falls most strongly on Jesus’ face, leaving us in no doubt that he is, or will be, the Light of the World. It also glistens on Joseph’s wrinkled forehead, creating a dramatic contrast of youth and age: however young we are, to this mortal end we will all eventually come.

Joseph is at work as a carpenter. The light falls on the twists of his shirt and his strong arms, employed in their physical labour: physicality captured and celebrated in the spiritual light. He is working with an augur, drilling a hole in a substantial beam of wood. A beam clearly stout enough to become part of a crucifix. The fate of Jesus lies already at his feet.

But Joseph is not really concentrating on his work. His brow is furrowed not with the strain of turning the augur, despite the glistening sweat, but by glancing up to look at his son. His eyes are focused upwards, in stoical restraint not expressing much emotion, but I sense surprise: surprise at what Jesus is saying.

Because if we look back now at the face of Jesus, we see that he is talking, his lips gently open, and his focus is on his father, not on his father’s work. This recalls the episode of Jesus in the temple astounding the elders. Joseph is indeed astounded as he glances at his son, reminded that his is no ordinary son, no ordinary apprentice learning how to follow in his father’s footsteps. He has another Father and other footsteps to follow.

But let’s look still more deeply. The left hand of Jesus shading the candle is wonderfully depicted as the light comes through the flesh, making his fingers glow with translucency. It is beautiful. One of Latour’s signature innovations. The spirituality of the flame animating the physicality of the flesh.

But look closer still. Jesus has dirty fingernails. This is my favourite detail of the painting. Partly the simple realism that boys generally have dirt under their fingernails; but what greater expression can you have of the idea of God made Flesh and dwelling among us? Those dirty fingernails, silhouetted against the spiritual light of the flame, capture the essence of our faith.