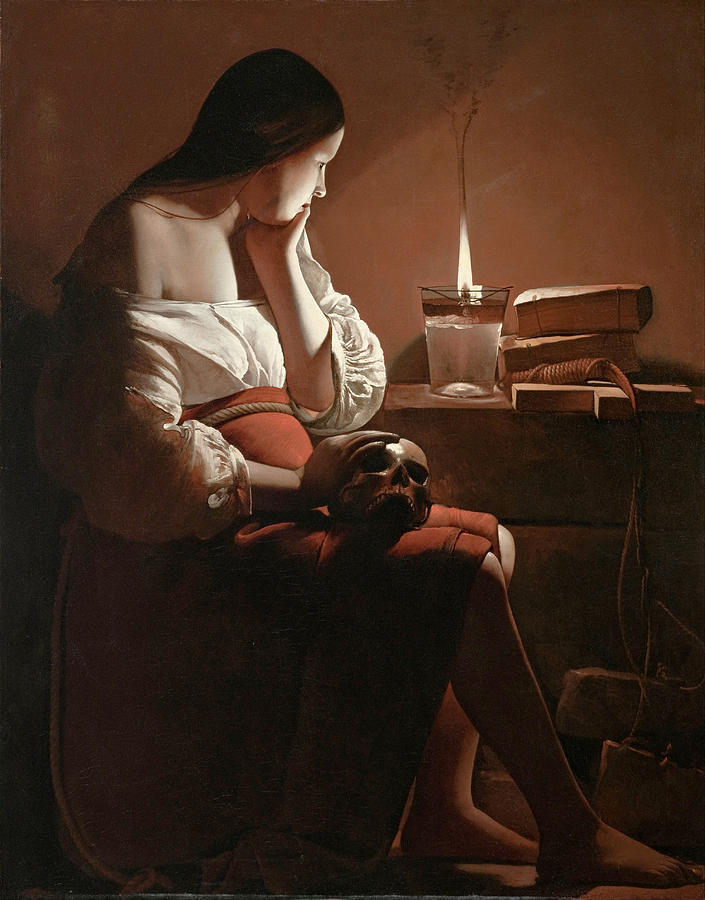

Madeleine at the Nightlight by Georges de Latour

Over the years, Mary Magdalen has provided the opportunity for some highly erotic forms of religious art.

She features in the Gospels as one of Jesus’ followers who was a witness to both his crucifixion and resurrection. In one of the non-canonical gospels, Philip’s, she is described as the disciple Jesus loved most and the one Jesus kissed on the mouth. But it was only in 591 AD that she became characterised by Pope Gregory as the repentant prostitute.

This gave artists during the High Renaissance and Counter Reformation the chance to depict her in agonising throes of penance, tears in her upturned eyes, while inadvertently letting her blouse slip from one of her breasts, as a titillating reminder of her sinful past.

De Latour does none of that. The emotion of this painting runs deeply and inwardly. It is lit by the smoking nightlight, which produces powerful contrasts of light and shade. It is a spiritual light, which also leaves two trails of sooty black smoke twisting upwards, as a reminder perhaps of the sinfulness of our mortality and the duality of our nature.

The calm, stillness of the composition derives from its structure of vertical and horizontal lines. The vertical elements include the flame itself, her right upper arm, with the shadow running down it, her left forearm, the rope running to the floor at the back of her skirt, and the angle that bisects her two shins and the hem of her dress. Perhaps the strongest vertical line, though, is formed by the shadow cast by her forearm onto her chest.

Horizontality is provided by the massive blocks which form a tomb-like table, the neckline of her blouse, her thighs. the heavy books and the stout cross that lies on the table. That cross also projects the third dimension directly at us, strongly foreshortened, bringing us into the space.

Set against that geometry is glorious delicacy in the handling of the light. It shines brightly on her face and lower forearm, but it also gently penetrates the sleeve to allow the upper part of her left forearm to glow beyond the shade thrown by the cuff. It brilliantly lights the convoluted folds of the sleeve of her right arm, through which shades of fleshly pink can be seen illuminating the shadows. Delicate shades of pink bring all her flesh to soft and inner life.

There are allusions to her past alleged sinfulness. Her blouse reveals one shoulder. She is wearing the red of the harlot rather than the blue of the virgin Mary, but it is coarse, penitential fabric; hardly a harlot’s dress. Her hair is long, which was frequently regarded sign of female sexuality, and indeed a strand of her hair has come loose, falling as a delicate sweeping curve in the composition, and perhaps hinting at moral looseness. Most worrying, though, is the bound rope on the table: intended for self-flagellation and with worryingly heavy weights attached to the end.

La Tour’s Mary does not look at us. She is not playing to the audience or indulging in her emotions. If anything, her face is turned slightly away as she stares into the flame and explores her inner being. The silhouetted curve of her head is in counterpoint to the horizontality and verticality of the composition. It is complemented by the longer and gentler curve of her hair as it sweeps past her temple, cheek and neck.

There is, of course, another spherical shape in the painting: that of the skull she is cradling on her lap. It is a classic ‘memento mori’ symbol. Remember death. Never lose sight of your mortality and your accountability at the last. The skull gleams in the light of the flame, as a highly polished and maybe even a much-loved skull. The fingers that cradle it follow its curve as if they have no knuckles. She is very comfortable with it.

But we are not done yet. There is one more sphere in the painting. Look at the rope that runs over her belly. How curved it is. Any mother will have noticed far earlier than I did that Mary is pregnant. If you like, you can read it as part of the myth that Dan Brown made use of in his Da Vinci Code, that Mary was carrying Jesus’ baby when he died. But I think that is a distraction. For me, I read the painting as Mary’s profound contemplation on the human condition: life past, life present and life to come. The skull, her own head and her womb, all brilliantly lit by the light of Christ and our own spirituality.